Forged in the Fires of Persecution: The suffering of early Salvationists

by Guest

by Rob Jeffery

It’s springtime and your local Salvation Army is about to have an outdoor Christian worship service. Just imagine: you meet at a bandstand in a nearby park or in a bustling town square. The band sets up and then plays a few introductory notes to warm their instruments. The audio/visual person quickly connects a microphone, a small soundboard, and a pair of speakers.

As the band plays, a few passersby approach, sit on nearby park benches, chat quietly, and listen to the music. The melodies are followed by a Scripture reading, a guitar and vocal duet, and then a short devotional by the speaker.

The listeners, who cycle in and out, are greeted by Salvationists who engage them in conversation as they offer SAconnects magazines and other literature. They tell them about the services that are available through their local Salvation Army. Later, after hearing the closing song and prayer, the church folk pack everything away. They thank God for allowing them to make a few but precious contacts. They’ve enjoyed an exciting experience, to say the least. After all, what’s better than an open–air service?

Growing pains

Now, go back in time and imagine yourself at a Salvation Army open–air service in the 1880s. This band is led by a 19–year–old pastor. Dressed in her blue uniform, she marches out of the church hall and into the street, to the beat of a bass drum. A small band of Salvationists, also in blue, follow her to the town center. As they pass a tavern, men with eyes made red from drink, watch. They and other men in public houses quickly file out after the marchers.

Grinning wickedly, they descend on the Salvationists and block their path. But in response, the band, that has been playing brass instruments for only a week or two, strikes up a tune. As their strain of “Onward Christian Soldiers” fills the air, a man from the tavern grabs a horn from one of the players, and throws it in the mud.

Another bleary–eyed drunkard rips the flag from the corps sergeant major’s (deacon) hands. Undaunted, the teenaged corps officer bravely plants her feet in front of the two biggest ruffians, and prays. In a surprisingly loud, confident voice, she asks God to change the hearts of these people.

But even as she prays, a well–aimed bottle strikes the trombone player. He rubs his head in pain. Despite the mob’s egging, no fists are raised in retaliation from the men and women in blue. Instead, the Salvationists form a circle and pray even more.

This is what open–air ministry looked like in the early days. It is quite a contrast between then and now. Back then, open–air work was brutal. Yet, the Army was refined in those fires of persecution.

As one of the most trusted charitable organizations in America today, many people are surprised to learn that The Salvation Army was once a persecuted movement. Born in London’s East End, William Booth’s Christian Mission (a precursor to The Salvation Army), provoked the ire of many a violent mob. Such opposition intensified when, in 1878, Salvationists, under the newly formed banner of The Salvation Army, began to wear uniforms, and attracted even greater attention from people who were spoiling for a fight.

The Skeleton Army

In England there arose an organized movement whose very existence was to harass and attack the ever–growing Salvation Army. In mockery, they styled themselves as the “Skeleton Army,” whose motto of “beef, beer, and bacca (tobacco),” countered the Salvationist’s motto of “soup, soap, and salvation.” While most skeleton army groups were formed by beer brewers and tavern owners, called publicans, some were organized by high–ranking members of society such as the mayors of Eastbourne and Folkestone. A book from long ago entitled The Old Corps, by Edward Joy, tells the harrowing story of the soldiers of Folkestone who battled the Skeletons frequently, as the latter group tried to steal the local Army’s flag.

At first, the police did little to protect Salvationists from the horrific violence of the mobs. In many cases they arrested the peaceful soldiers and officers whom they blamed for agitating the townspeople with their marching in the streets and open–air music.

Journalist Bethan Bell (BBC News), in a story about the Skeleton Army in the UK entitled “Menace to sobriety: when Salvationists fought Skeletons,” notes how the English right to freedom of expression came about when they began to challenge in court the arrest of Salvationists. Bell wrote that the police tried to “… ban marching with music on a Sunday because it attracted Skeleton troublemakers. But it was later ruled that a lawful activity (marching with music on a Sunday) was not made unlawful by the unlawful actions of others (Skeletons rioting).”

Forging ahead in the U.S.

Meanwhile in the United States, Salvationists were also suffering because of the public expression of their faith. In 1879, the Shirley family had to deal with disorderly persons who interrupted their meetings at the Philadelphia Salvation Factory. Commissioner George Scott Railton also met official opposition from the mayor of New York, who would not allow the Hallelujah Lassies to march in the streets.

Furthermore, James Kemp, or “Ash Barrel Jimmy,” the Salvation Army’s first convert in the U.S., received frequent beatings at the hands of his former friends in the Bowery when he went back to preach the good news. In Greenport, Long Island, the corps was burned down by a riotous crowd. Staff Captain Joseph Garabedian or “Joe the Turk,” was jailed over 50 times for preaching outdoors. In Boston, Commissioner Samuel Logan Brengle was hit in the head with a brick.

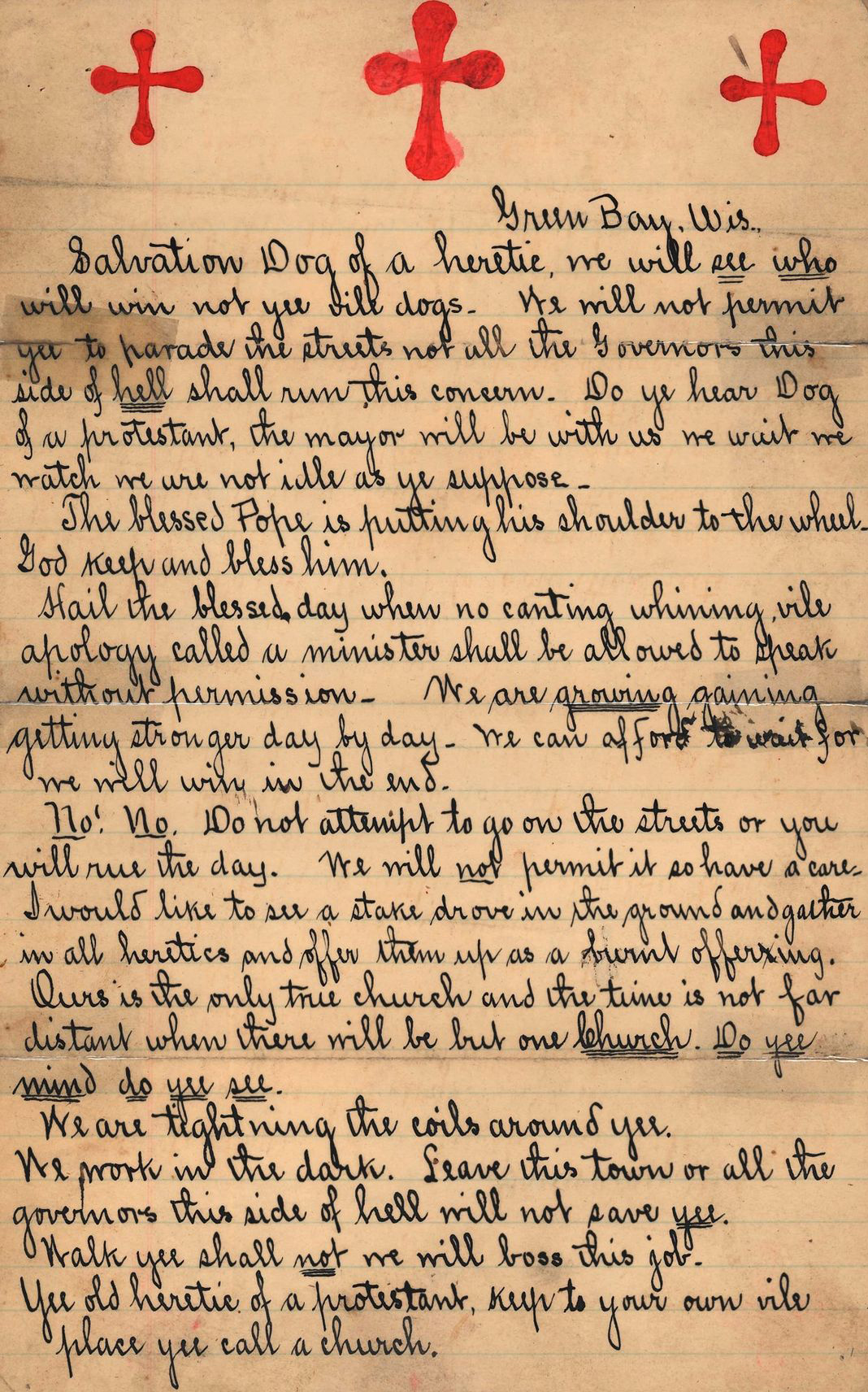

Displayed in The Heritage Museum archives, located at the Army’s USA Eastern Territorial Headquarters in West Nyack, N.Y., a letter from the 1890s by an anonymous writer threatens The Salvation Army in Green Bay, Wis. It reads, “I would like to see a stake drove in the ground and gather in all the heretics and offer them up as a burnt offering.” Praise God that, despite this threat, The Salvation Army flag still flies in the city of Green Bay.

Thankfully, by the late 1890s, most of the hot spots of persecution were cooling down. Through their sheer tenacity and belief in a divine mission, Salvationists won over many of their critics. Perhaps those early Salvationists didn’t just see a mob of violent men and women, but individuals whose lives needed to be touched with the love of Christ.

From enemy to emissary

Commissioner Charles Jeffries, famed Salvation Army missionary to China, was the leader of a group of Skeletons prior to his conversion. Someone in a band of Salvationists, on the receiving end of his hateful actions, knew that deep inside this young man was a soul waiting to blossom into new life. By their love, they overcame the hatred shown to them, and won many souls to Christ. William Booth said in 1883, “We make the very enemy help us fill the air with our Savior’s fame.”

By the early 1900s, police and other civil authorities began to recognize the Army’s witness as something positive. Eventually, most Salvationists in the U.S., could march in the open air with virtually no opposition and enjoy the protection of law enforcement.

The Salvation Army has come a long way since those early days of trial and opposition. However, in other parts of the world, Salvationists still operate in countries where they are not legally recognized, and even experience bouts of persecution through religious and sectarian violence. May we use our freedom to advocate on their behalf and for all persecuted Christians around the globe.

Read more from this issue of SAconnects.