Gaining and Keeping Trust

by Guest

by Rob Jeffery

A history of transparency in The Salvation Army

One of the main expectations any charitable organization must live up to is transparency—to be an “open book” to the public to ensure that it’s worthy of being trusted. When that organization is also a religious movement modeled after the gospel of Jesus Christ, gaining and keeping the public’s trust becomes even more important.

Long before The Salvation Army came into being, Jesus spoke extensively of the need for His followers to be open and transparent. He wanted His disciples to be trustworthy through their words and deeds when He said, “Let your yes mean yes, and your no mean no” (Matthew 5:37, CEB). Jesus spoke of the importance of paying a worker his due and sent His missionary disciples out in twos for mutual support but also accountability (Luke 10:1–12). A model of transparency and openness is still practiced in the Church today. In the history of the Church as recorded in the Book of Acts, we see what happened to the unethical Christian couple, Ananias and Sapphira, when they lied about how much they gave to the Lord’s work. Their deceit grieved the Holy Spirit (Acts 5:1–11).

Checks and balances

In founding The Salvation Army, William and Catherine Booth created a movement that ran in very defined ways. William was no doubt in charge, but there were systems of accountability present from the start.

For the 13-year period in which the Christian Mission operated (1865–1878), William Booth was its general superintendent. There were committees with rules and procedures on how the mission was to be governed—similar to the structure of the Methodist New Connexion, the denomination from which the Booths came. The mission members later voluntarily gave up their autonomy in favor of having Booth take a more direct, top-down role in leadership of the newly styled Salvation Army. General Booth (dropping the superintendent title) would have the final say on every policy and action taken. But committees would be replaced by “war cabinets” that could speak to the General’s command authority, refining ideas to make them more effective and preventing missteps.

In Victorian England, a journalist wrote a tabloidesque story claiming that Booth and his followers were following the mysterious dictates of a “secret red book.” The book in question was none other than The Salvation Army’s Orders and Regulations, available to anyone who wanted to read it. But the finances of the growing movement were the greatest source of contention among the Army’s critics. False charges of financial mismanagement abounded to the point where an awful caricature was printed by a London newspaper, making Booth look like a greedy money grubber. Such a depiction could not have been further from the truth.

Following the financial recordkeeping of the Christian Mission, Booth put in place a rigorous system full of checks and balances. Funds were centrally controlled out of divisional and territorial headquarters, and at the corps level, local officer positions such as corps treasurers were created to be a second set of eyes watching over Salvation Army funds. And Booth paid top dollar to some of England’s top accounting firms to audit every budget line on The Salvation Army’s ledgers. It was vital that as public support of the Army increased, the same public could trust the Army to use its money wisely.

The Salvation Army officially launched in America in March of 1880. Commissioner George Scott Railton discovered that within a few weeks of their arrival, an imposter calling himself General Haskell was holding camp meetings throughout the Midwest, soliciting funds for The Salvation Army. Railton wrote to the newspapers that this man had no connection with the real Army, but it was difficult to undo the damage. He could, however, ensure that the real Salvation Army was above reproach in its dealings, financial or otherwise—which is why on the first handbill Railton created to advertise a service at Harry Hill’s Variety Theatre on March 21, 1880, he noted at the bottom of the bill, “Admission 25 cents. Not a cent of the money goes to any member of the Army.”

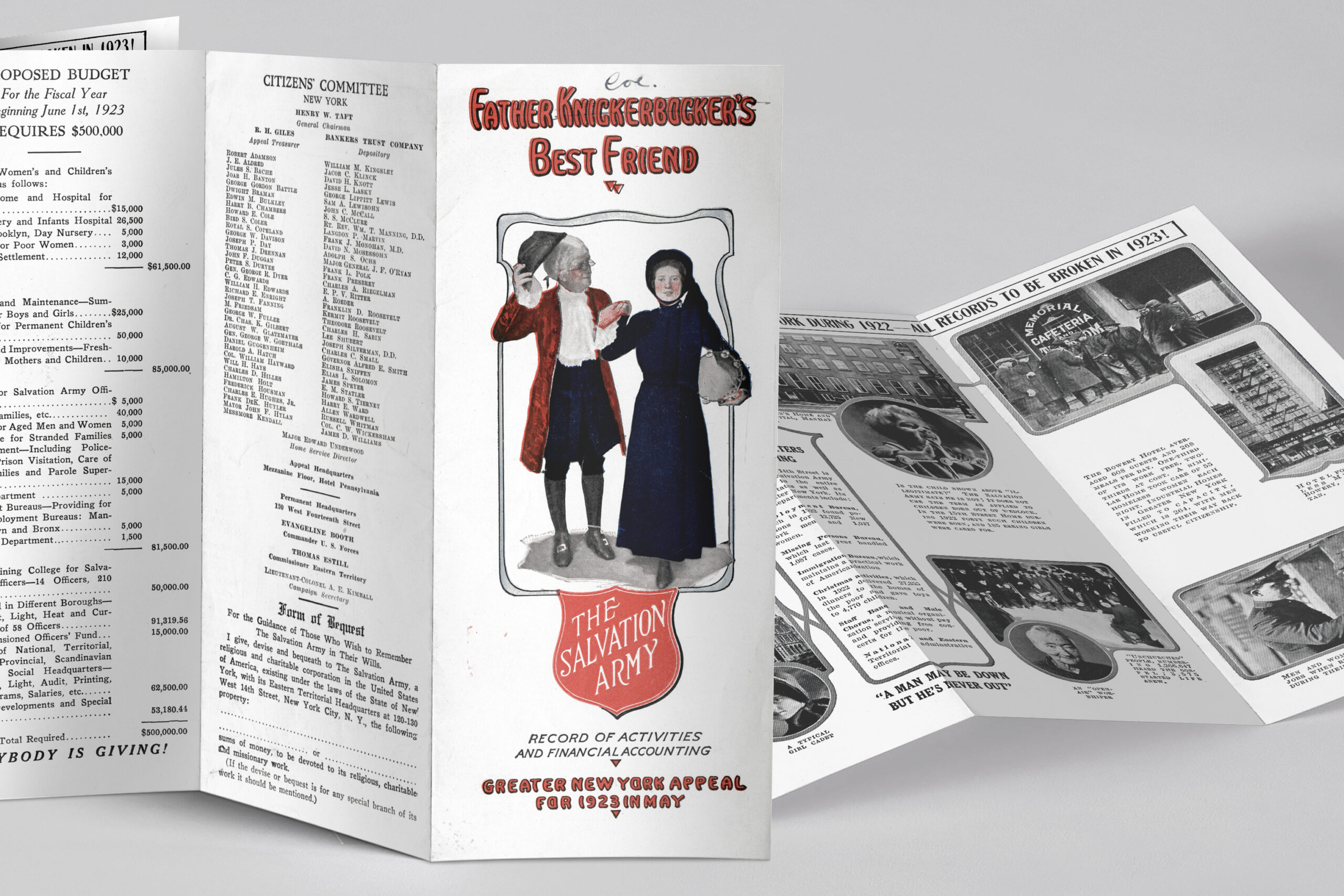

This 1923 pamphlet highlighted The Salvation Army’s work in the greater New York area and provided financial information to the public.

A spirit of openness

As time marched on, The Salvation Army got better at demonstrating its transparency by combining the auditors’ findings with promotional material that showed the Army’s work in the community. For instance, a pamphlet from 1923 highlights The Salvation Army’s work in the greater New York area. On one page it documents the many services provided by Salvationists in New York City; on the other it shares details of the accounting ledger, including expenses and income and the proposed budget for next year. The auditors’ certificate and signature tell whoever is interested that these facts and figures were verified by the auditing staff of “The Audit Company of New York,” which became part of Price Waterhouse—one of the “big four” accounting firms still around today.

Today, transparency has never been more important. The Salvation Army takes many steps to establish a spirit of openness and visibility in its dealings with the public. Nationally recognized programs such as KeepSAfe make sure that children and youth under the Army’s care remain safe at all times. Meanwhile, sophisticated yet easy to use financial management programs help everyone from corps officers (pastors) to command heads properly account for spending.

The Salvation Army has a rigorous auditing system, so the public can trust their donor dollars are going to the right places and helping people truly in need. Every division in the USA Eastern Territory publishes an annual report that gives the public a thorough overview of the Army’s work in the division with all the accounting details. Annual reports are also published territorially and nationally.

In 2004, the newly renovated International Headquarters (IHQ) building for the worldwide Salvation Army reopened in London, England. IHQ had occupied that historic site on 101 Queen Victoria Street since 1881. The redesign featured a beautiful glass building with interior glass walls. Even the office of the General, the international leader of The Salvation Army, was open and visible to all—as it still is today—on the public-facing ground floor of IHQ. A spokesperson on behalf of the architectural firm said their goal was to “design a building where transparency is a theme.” Many Salvationists work hard every day to be certain that The Salvation Army will always uphold its reputation as a transparent and trustworthy organization, meeting human need in Jesus’ name.

Rob Jeffery is director of the Heritage Museum in the USA Eastern Territory.